When it comes to discussing Kees’ musical career and its place in history there is a lot to say. We are slowly approaching the end of the 80s and 90s and those were characterized by a series of fascinating changes within the world of music. This encapsulates more than one might think. Yes, it is true: the history of music is heavily connected to the technological, political, and economical developments that ran alongside of it. Punk, gabber, techno, and hip-hop: four genres which in many respects differed, yet in many ways shared those features that Kees was always naturally drawn to: energy, power, and aggression. Lars too always found himself subconsciously drawn to music with just these characteristics. However, both have had a radically different experience of the world of music and its place within society during their respective times, even though Lars can be somewhat of a boomer when it comes to passing judgement on his generation and their many indulgences. Keep reading for a confrontation between the young and the old, to learn how histories give shape to corresponding understandings of music.

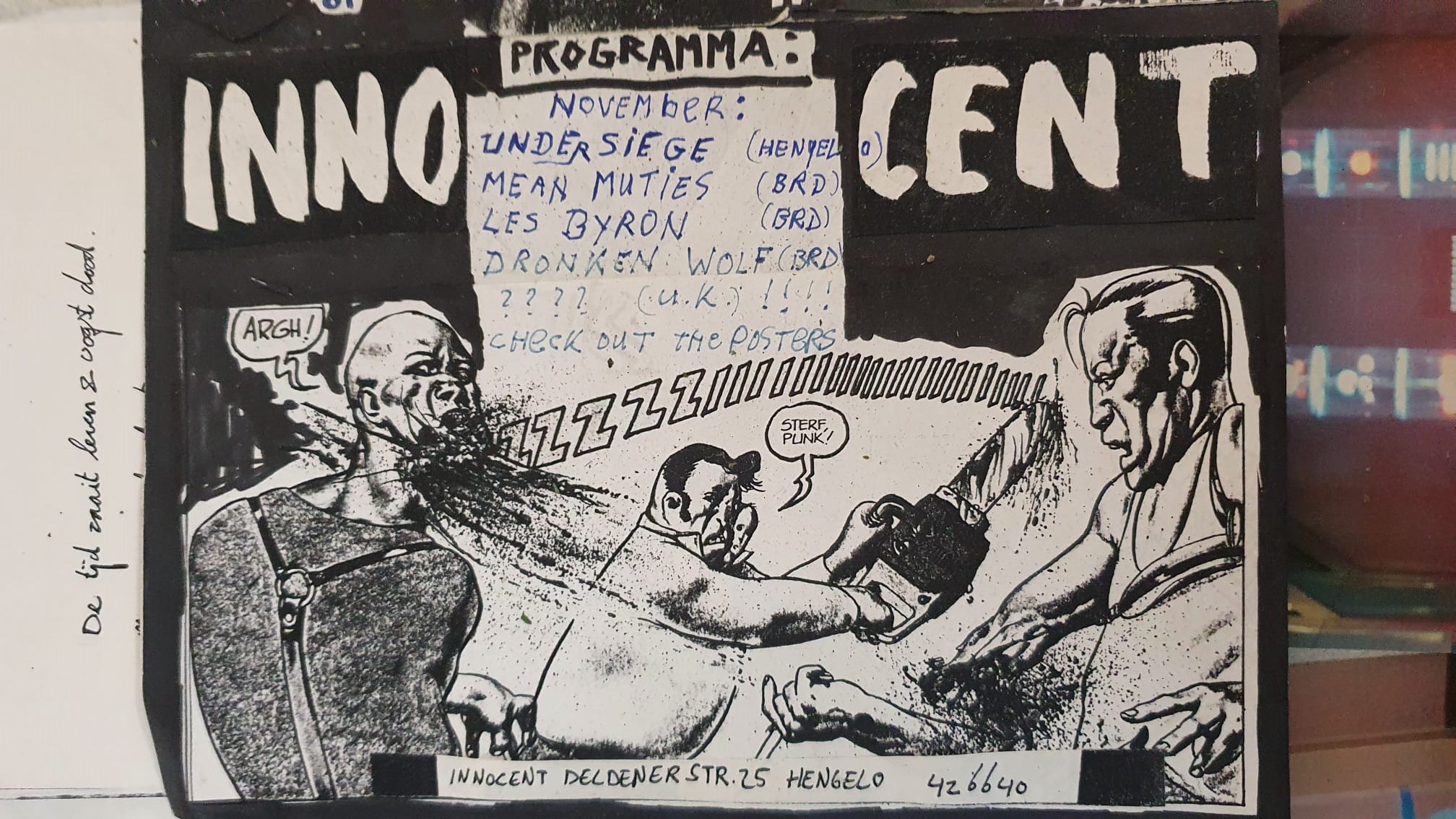

Kees: it might be nice to start here since I have a lot of beautiful archive materials on this subject [Kees points to multiple fanzines and pictures of bands wearing sinister adornments and masks]. We used to organize international, underground hardcore band nights in the Innocent youth center in Hengelo. This was a place where local enthusiasts and activists came together during the heydays of squatting; and squatting was only of our undertakings alongside a full agenda of activism. Every first of May we used to take a convoy of busses to Berlin to protest against the institution of capitalism. During band nights we transformed the Innocent into a small underground venue. These nights were organized alongside the release of a well-received fanzine, titled Kreis Hengelo. Therein we reported on all the new music that came out, ranging from death metal, to grindcore, to punk, and the Norwegian black metal that brought about a wave of church burnings. All the new releases were mentioned in there. Music by Napalm Death, Carcass, Terorrizer. The list was endless.

Our band nights were well visited. Every time, another politically engaged band would climb the stage: Discords, Störfall Mensch, Everybody Dead, Doom. There was a lot of mosh pitting and screaming, but also a lot of sensible talk. People engaged in discussion and talked about ”what the f*ck was going on in the world”. For an autonomous artist during this period, surrounded by a network of like-minded people, the question was inevitable. Punk is ats core a political genre, expressing a sentiment that can be found the world over. All these bands that came to Innocent were united by mutual anger and dismay concerning international developments. The network we gathered around Innocent and Kreis Hengelo knew bands from Australia, The United States, and even Brazil. Fun fact: during that time we actually squatted the building right next to Innocent and this became the first night club of PLANETART, titled Deaf Club Pussy Heaven.

”Both genres had their own sound powerful enough to gather around a mass of fanatics. Punk and guitar music had this rawness, this fuzz that emanated an incredible energy. If Jimi Hendrix or Kurt Cobain would grab their guitar you got instant goose bumps.”

So in the 80s punk and guitar music were thé mainstream genres for the young generation. They were however, slowly overtaken by the emerging computer music of that time. I was keen to go along with this change because the new way these genres brought the youth together was fascinating to me. Both genres had their own sound powerful enough to gather around a mass of fanatics. Punk and guitar music had a rawness; a fuzz that emanated an incredible energy. If Jimi Hendrix or Kurt Cobain would grab their guitar you got instant goose bumps. It was a harsh sound that penetrated to the bone. It seems to me that the early Rolands – the 303 and 909 – took this as an example, and that conviction is not so far-fetched considering the fact that these instruments were originally meant as band supports on stage. The Roland TB-303, released in 1982, was by the producer itself regarded as a total failure. However, it was the 303 that eventually produced the revolutionary acid-bass sound from which a completely new genre sprang. The groove and raw power of the electric guitar and this new synthesizer with its sharp wowowowows were eerily comparable in that respect. Due to the high frequency and the dissonance thereby produced, one ended up with an abrasive sound that was still somehow pleasant. Such intensity could get whole dancefloors moving. For the new electronic sounds to really assert themselves as independent genres, the 909 was just as essential. The Roland TR-909 was a drum computer that just like its partner – the 303 and 909 could always be found together on the table of an acid-bass producer – was definitive of the newly developed genres of house, techno, and acid. Which all by the way had at least part of their origins in Chicago and Detroit.

‘’…my performances were de facto an entire allegory for what was happening back then. The boundaries between humanity and technology were becoming increasingly smaller. Thus, when the crowd saw me on stage as a foreman, I wanted them to see an actual robot or cyborg.’’

I always kept this new music and the whole culture that enveloped it close to my art practice. I ran down, even broke a lot of Rolands in my time. The difference between me and a mere producer however, was that I included the music into a holistic performance. You could find me behind the mic covered in body art to feel more at home on stage, looking like a robot in the midst of a superstructure of hardware and cables. None of me and my band’s performances were what they were without the inclusion of projections and video imagery. I would not be able to tell you whether this was conscious or subconscious, but my performances were de facto an entire allegory for what was happening back then. The boundaries between humanity and technology were becoming increasingly smaller. Thus, when the crowd stared at me on stage as a foreman, I wanted them to see an actual robot or cyborg. I wanted them to be no longer able to distinguish the human being from the technologies it used. This was all the same with the media barrage that we sent flying toward the audience. The boundaries between real and unreal were already fading back then. On stage, my band and I would portray the characteristics of the new society. Music and this revolutionary way of performing herein were one and the same. Both were shaped by a technological substructure that had become inextricable with every aspect of human life.

This was only the first part of this deep dive into the history of music. Next time, Kees and Lars elaborate on the role of music within politics and how the relationship between these domains has changed. Is the new generation simply no longer willing to fight for their future?